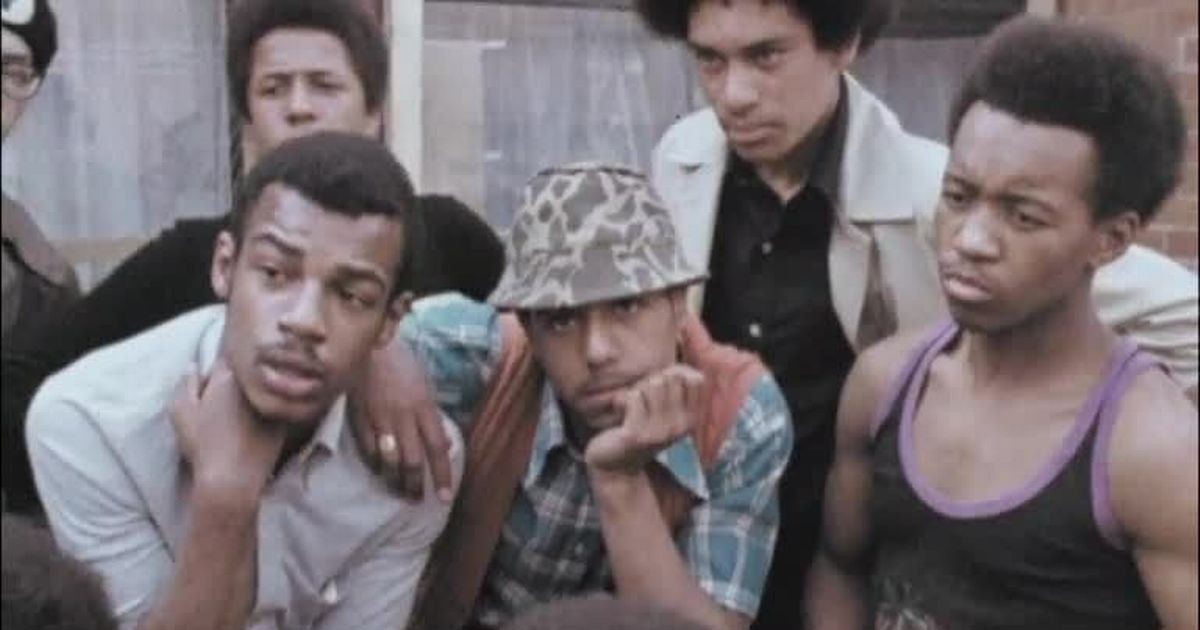

Youngsters being interviewed for television in the aftermath of race disturbances in 1972

With Black History Month upon us, Getintothis’ Janaya Pickett reflects on her own multicultural past and the legacy of Liverpool’s Afro-Caribbean community.

Black History Month is approaching and with positive intentions we at Getintothis thought it only right to dedicate some space to black voices involved in the local music and arts scene.

We approached promoters, artists and venue managers with questions about race relations in the arts community and the black experience more generally.

The vast majority of the people we contacted did not wish to comment.

Only two were wiling, in fact. And both noted that although black culture holds its’ own in Liverpool, the community in the city itself is underrepresented in the arts. Both noted that many people involved in organisations engaged with the black community are not from Liverpool at all.

One of those who declined to comment said the issue was ‘a can of worms’ they simply couldn’t open. The myriad of difficulties they are confronted with is endless – so they wouldn’t know where to start.

Another felt that speaking out about the struggles they had faced would jeopardise potential professional opportunities.

We were disappointed that people didn’t feel free to talk, but we understood why. Race is still, in 2016, a controversial issue highlighted at present by the refugee crisis, Brexit and a resurgence of black politicism in the form of Black Lives Matter and other campaigns.

Also, in keeping with the times, there has been a resurgence of right wing extremism that holds archaic ideas about race based on pseudo-sciences debunked quite some time ago.

In August last year, far right group National Action organised a White Man March in Liverpool and an anti-fascist counter demonstration was quickly organised that would eventually go viral and eclipse the attempts of the racists.

Us Scousers get real territorial and the attitude from the counter demonstration, the majority of which were white men and women, was “not in our city“.

As the placards proclaimed, Liverpool was ‘built on immigration‘. The White Man March was abandoned and police dispatched to ‘protect‘ fascists as they waited in lost luggage at Lime Street – for transport back to whatever rocks they crawled out from.

A mainstream demonstration is one thing but to speak personally about the black experience is something else, clearly. In the face of right wing extremism such as National Action we stand united. But if we broach the topic of everyday prejudice on a local level there’s a risk provoking discomfort and anger.

Evidently people fear speaking up or speaking out: They don’t want to appear to be complaining or worse as an ‘angry black with a chip on their shoulder‘. That old chestnut.

In the absence of other voices on the matter we decided to the focus on Black History Month in Liverpool itself which is integral to the history of our city.

Perhaps we can go some way to understanding race relations by looking at the past. How much do we care to remember?

A Scene Unseen – the Afro-Caribbean artists that lit up Liverpool music

Liverpool has the oldest black community in the UK. In fact back in the day you could walk along the dock road and hear every language imaginable.

The world in one city; A global port. ‘Sailortown’, it was dubbed. At one point, outside of the growing business district, there were churches, brothels, lodgings and ale houses en masse. It all sounds very swash-buckley, but the reality is quite sobering.

Aside from the city being developed off the back of the slave trade it is a fact that slaves were sold in Liverpool. Not in the same way as in the US, but casually, in small numbers in coffee houses and as domestic servants.

There were also free black men and women in Liverpool as early as 1710 and over the years a community developed. During WWI this black population increased and once the war was over so did racial tensions.

The race riots of 1919 are a little known part of Liverpool’s history. Indeed racism seemed to reach its zenith globally as well as in the UK post WW1.

There were not only riots in Liverpool, but in Cardiff, Glasgow, London and other port towns.

Liverpool’s riots erupted around the modern day Chinatown area where crowds in their hundreds looted, burned buildings and beat any black person they could find.

Telegram from central government to the Lord Mayor of Liverpool RE ‘Coloured British Subjects’ in the city

Charles Wootton, a 24 year old Bermudan sailor, was chased by said crowds down towards Queen’s Dock. He was either pushed or jumped in to escape, but once in the water was pelted with rocks until he drowned.

His body was fished out later that evening once the crowd had dispersed. Nobody was charged but an event like this on British soil was unprecedented.

Newspapers at the time called it a ‘lynching‘. There has recently been a memorial laid near the dock by documentary filmmaker David Olusoga, recognising its significance in the history of race relations in modern Britain.

Literary organisation Writing on the Wall have for the last eighteen months been researching an archive of letters pertaining to the 1919 riots and the state of race relations in Liverpool at the time.

Donated by community activist Joe Farrag and with the help of a small group of volunteers WOW have catalogued and digitised these records to view online.

The archive has now been donated to Liverpool Central Library for free public use.

It is a disturbing history but nonetheless one that is important and can teach us about the present.

The pattern of economic crisis, unemployment and lack of housing manifesting itself in blame games and racial tensions is timeless.

Yes, thankfully the events and attitudes of 1919 seem alien to the majority of people today but there are always those patterns – conditions in which racism is most likely to grow.

XamVolo: The BRITs’ disregard of black artists and grime is a form of exclusion

Local historians such as Ray Costello, Mike Boyle, John Belcham and organisations like Writing on the Wall and National Museums Liverpool have documented periods of history that are unknown to the vast majority.

Some may even question the validity of Black History Month or why said history is so important to black identity. Well, we suppose if your identity is questioned frequently the subject of your identity would be of interest to you.

Although Liveprool’s black community is the oldest in the country, it constitutes only 2% of its population.

It’s easy to understand how growing up black in such a place, with those odds, could be troublesome. This writer in particular grew up confused when asked where she came from having lived in Liverpool since birth. When I was older I looked to find out, like a low budget Who Do You Think You Are?

My Mum’s family were white, English as you like, traced back to the mid-1700s in and around Liverpool.

My Dad’s family were black, his grandfather settling in Liverpool after serving the British West Indies Regiment in WW1: Arnold Hinds was 18 or 19 at the time and would have experienced the riots of 1919. Black ancestors on my Dad’s maternal side dated back further in Liverpool, some to the late 1800s.

In a Dorothy Gale type of way I realised that this mystical sense of belonging I wished to have was right in my own backyard.

I felt validated not only in my black heritage, but in my Scouseness and by the fact that my ancestors had been residents of Liverpool pre-Liver Building (1911). You can’t get more Scouse than that.

Understanding the history of things makes you better equipped to deal with these social and political situations. In my personal opinion Liverpool’s black community is still largely isolated and indeed insular and in turn often goes ignored. Concentrated within a few square miles it is a tight knit community but also a stagnant one. On the surface we embrace diversity but how far is that put into practice? Why do we then find it so difficult to discuss?

It is thought that the 1919 riots were somewhat of a watershed moment for race relations in Liverpool and that after WW1 a ‘colour bar’ was erected that sought to purposefully disenfranchise the black community.

The ramifications of the past run deep and similar issues are still being argued today.

We can only really conclude that we think a continuing engaged discussion on race is vital as we’ve come an awful long way, but there is still ways to go.

Black history is not exclusive but essential, especially in cities such as Liverpool.

You can check out the Great War to Race Riots Project page here.

On October 7 Ray Costello will also be holding a talk at the Maritime Museum as part of Black History Month about his recent book.

Black Tommies is a record of British born black soldiers that served in WWI. For more information click here.

[paypal-donation]